Eight years ago this week, cartoonist Alex Norris posted a message a three-panel webcomic that was probably intended as a thinly veiled commentary on the 2016 election – but one that is even more relevant in today’s political world.

In it, a character, surrounded by furniture and various trinkets, declares, “I want things to be different,” and then throws everything across the room. Now surrounded by a messy pile of broken stuff, the character delivers the punch line: “Oh no.”

The only thing we can say with certainty about 2024 is that voters worldwide want things to be different. Time will tell how that turns out.

Donald Trump’s victory and Republican takeover of the U.S. Senate in this week’s elections joined a remarkable trend of political turnover in the democratic world this year. The most interesting thing about this trend is the lack of a clear ideological shift behind it.

Voters don’t seem to be turning against progressive or conservative parties, and (despite what Tuesday’s results look like in America) the trend doesn’t seem to be perceptibly right or left. The Conservative Party was hit hard in Britain’s elections this summer, when the left-wing Labor Party claimed a majority in parliament for the first time since 2010. Meanwhile, the German Social Democrats (a left-wing party) was bulldozed in the European Parliament elections.

The trend continues beyond the US and Europe, and includes a crushing defeat suffered by the conservative party of South Korea in April, and the loss by the liberal party African National Congress in South Africa, who had ruled for three decades (and was responsible for ending apartheid). Cast your gaze back to 2023, and the flight anti-establishment disruptions includes the historic victory Through Javier Milei in Argentina.

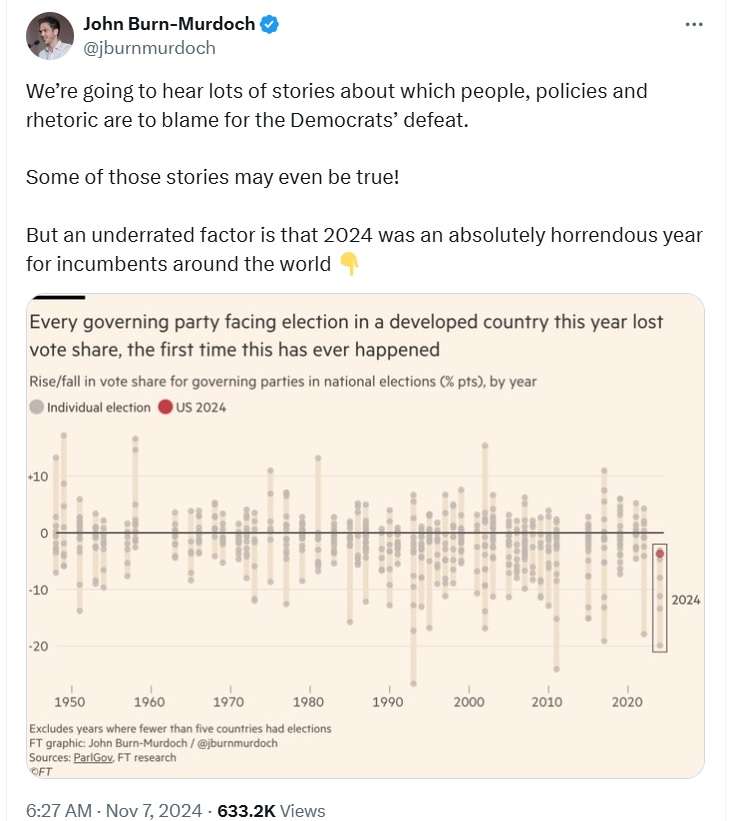

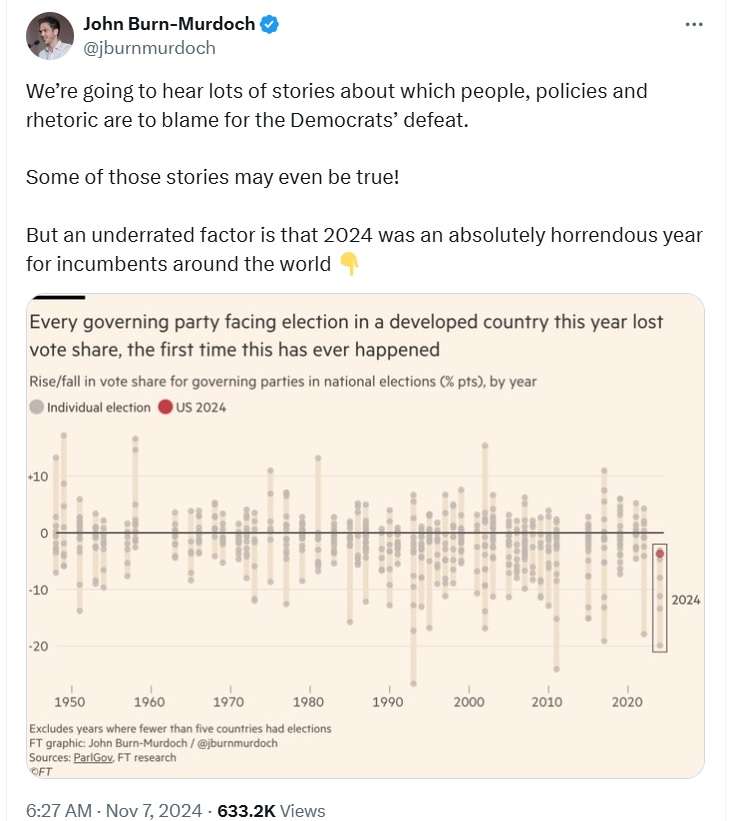

Even in places where ruling parties have remained in power this year, they have won a smaller share of the vote than in previous elections. That includes races in IndiaJapan, Belgium, Croatia, Bulgaria and Lithuania, according to an analysis of the election results by the Financial times.

John Burn-Murdoch, the data reporter who compiled these figures for the Financial times, says this series of losses among incumbent parties is unprecedented in the modern world. “This is not only the first time since (World War II) that all incumbent parties in developed countries lost their vote share,” he said. posted on X. “It is the first time since these data were first recorded in 1905. Essentially the first time in the history of democracy (universal suffrage began in 1894).”

(Source:

(Source:

To enrol The Atlantic Ocean in AugustDerek Thompson identified this trend as the “demise of the establishment, the disease of the incumbency, a sweeping revolt against the elites” and a legitimate threat to Vice President Kamala Harris’ campaign. “The voters of the world are tired of who’s in charge,” he concluded.

Simplisticyou could look at that global trend and use it as an excuse for Harris’ defeat (and Democrats’ poor performance across the board) in this week’s election. Is she just the latest victim in a wave of anti-establishment sentiment that has swept the democratic world in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic?

There’s probably a better, deeper explanation. Burn-Murdoch’s theory is that “people really hate inflation.” That’s likely a big part of it. Historically, sharply rising prices have been associated with various periods of social and political unrest I have written about on the pages of Rode. Inflation breaks people’s brains, and that anger tends to wash away ideological considerations that might drive voting preferences in more normal economic times.

The dissatisfaction that voters register with incumbent parties also likely reflects an ongoing problem in the democratic world — and one that Harris’ campaign perfectly illustrated. It seems that established parties no longer have big ideas, or at least don’t have big ideas like the voters like.

Harris struggled to articulate what could be called a compelling vision for the country’s future. Economically, she tied herself to the failedBidenomy‘ that helped cause inflation. Other than that, she offered little other than carefully calibrated clichés.

Trump, for all his many faults, certainly cannot be accused of lacking big ideas. Unfortunately, some of these (such as mass deportations) are morally objectionable, while others (such as tariffs) are likely to fuel further dissatisfaction with rising prices.

We will not reach the end of the anti-incumbency trend in global politics until a party in power gives voters a reason to keep them there. That will likely require the political parties that emerged victorious from the chaos of 2024 to look beyond the next campaign cycle and articulate an optimistic vision for a richer world.

I don’t pretend to know what that will look like, but I’m deeply skeptical that the zero-sum, nostalgia-driven politics Republicans are currently offering will be. Once in power, Trump will become the establishment and the countdown to voters who will turn against him will likely begin.

That’s the problem with the “I want things to be different” moment: No one who gains power can expect to keep it for long. Rather than an excuse for Harris’s loss, this global trend is better understood as a warning to those celebrating Trump’s victory.