More than a decade ago, it seemed like the tide might be turning against the pervasiveness of sexual violence on campus. In one Letter from 2011Under President Obama, the Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights charged universities with taking effective steps to end sexual violence, a form of sex discrimination prohibited under Title IX.

Over the next few years, the issue of campus sexual violence gained the attention of the U.S. government. In March 2013, Obama signed the Campus Sexual Violence Elimination Act, which, among other things, required many universities to offer campus-wide sexual violence prevention programs. Over the past decade, four-year colleges have established prevention programs that educate students about consent regarding sexual violence. In 2022, President Biden reauthorized the Violence against Women Act and called for the development of the Interagency Task Force on Sexual Violence in Education, which Congress charged with providing recommendations to educational institutions on best practices in sexual violence prevention.

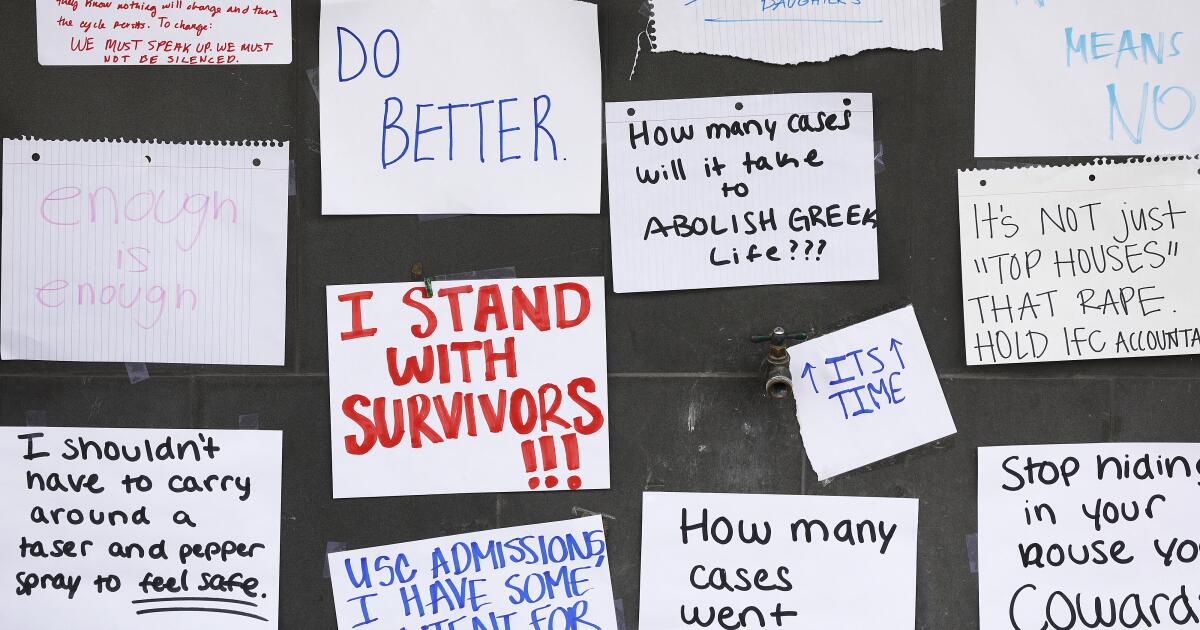

Yet this increased government guidance and increased institutional efforts have not yielded much concrete progress. “The conversation has gotten more intense, but not necessarily more productive,” said Sara Lipka, editor at the Chronicle of Higher Education, wrote. While there is still debate about the oft-repeated statistic that 1 in 5 women experience non-consensual sexual contact in college, this is not the case. convincingly debunked. Research shows that the risk of sexual abuse is often greater for students with multiple marginalized identities.

Attempts to prevent sexual violence often fail because of a one-size-fits-all approach. Typical prevention programs focus on the meaning of gender and ignore the meaning of race. As a result, they often fail to support women of color.

Take alcohol consumption, for example. Because it is one of the most studied risk factors for experiencing sexual violence in college, institutional prevention programs place a hyperfocus on the link between alcohol and sexual violence. But this focus isn’t as helpful for many women of color, who, studies suggest, drink less often than white students and experience less alcohol-related violence on campus. The decision to drink less is tied to racial identity – some students, for example abstain from alcohol to avoid hostile encounters with campus police.

There is also an intense focus on Greek life as a risk factor, as sorority membership has been linked to a higher risk of experiencing sexual violence. But because of the racist history of traditional Greek life on campus, many women of color are still excluded from membership in Panhellenic sororities, which are predominantly white.

Concerned about the exclusion of their perspectives from prevention programs, I interviewed surviving women of color and asked them directly: What did they see as a primary risk factor for experiencing sexual violence on campus?

Their answer is instructive for all: a lack of comprehensive sexual health education.

Nearly all the women I spoke to were exposed to abstinence-only sex education before college. As one interviewee said, the sex education she received taught her, “Just don’t do it. That’s the best.” This education, or lack thereof, influenced women’s vulnerability to sexual violence. Years of research demonstrate an abstinence-only curriculum doesn’t work — it does not reduce the amount of sex young people have and does not affect their contraceptive use. Instead, it often promotes a culture of fear, shame and silence sexual health and fails to prepare students to recognize and form healthy adult relationships. It too strengthened discrimination and victim blaming.

Alternatively, an approach that does not teach students strict abstinence, but comprehensive sexual health, could act as a protective factor against campus sexual violence. One study at Columbia University found that female students who received sex education before college, including training on how to say no to sex – also called refusal skills – were less likely to experience penetration in college than students who did not receive this training. This more in-depth training would help all students, including young men, better understand consent and respect their own boundaries and those of others.

The lack of education about refusal skills, or most other aspects of sexual health, that I found in my research was unfortunately not surprising: only 30 states and the District of Columbia public schools needed provide sex education. Seventeen states teach abstinence-only, and more than half of the states require schools to emphasize abstinence. The future for sex education does not look bright: the first Trump administration promoted abstinence-only education, a push that may return with a second Trump term.

And higher education cannot always close this gap. One woman I interviewed recalled how her university’s mandatory prevention training lasted ten minutes and focused only on consent. Another survivor told me that the prevention education video she had to watch at school featured “all these students.” … All (the actors in the video) were white. They were all heterosexual. And (they) spoke in a way that assumed everyone was just like them. The material was not relevant to her.

The lessons I learned from my conversations with women of color can benefit all students and institutions: A more effective way to prevent sexual violence is to teach young people early about safe and healthy sex and to consider identity in this comprehensive education.

Jessica C. Harris is an associate professor of higher education and organizational change at UCLA and author of “Hear our stories: campus sexual violence, intersectionality, and how to build a better university”, from which eThis piece has been edited.